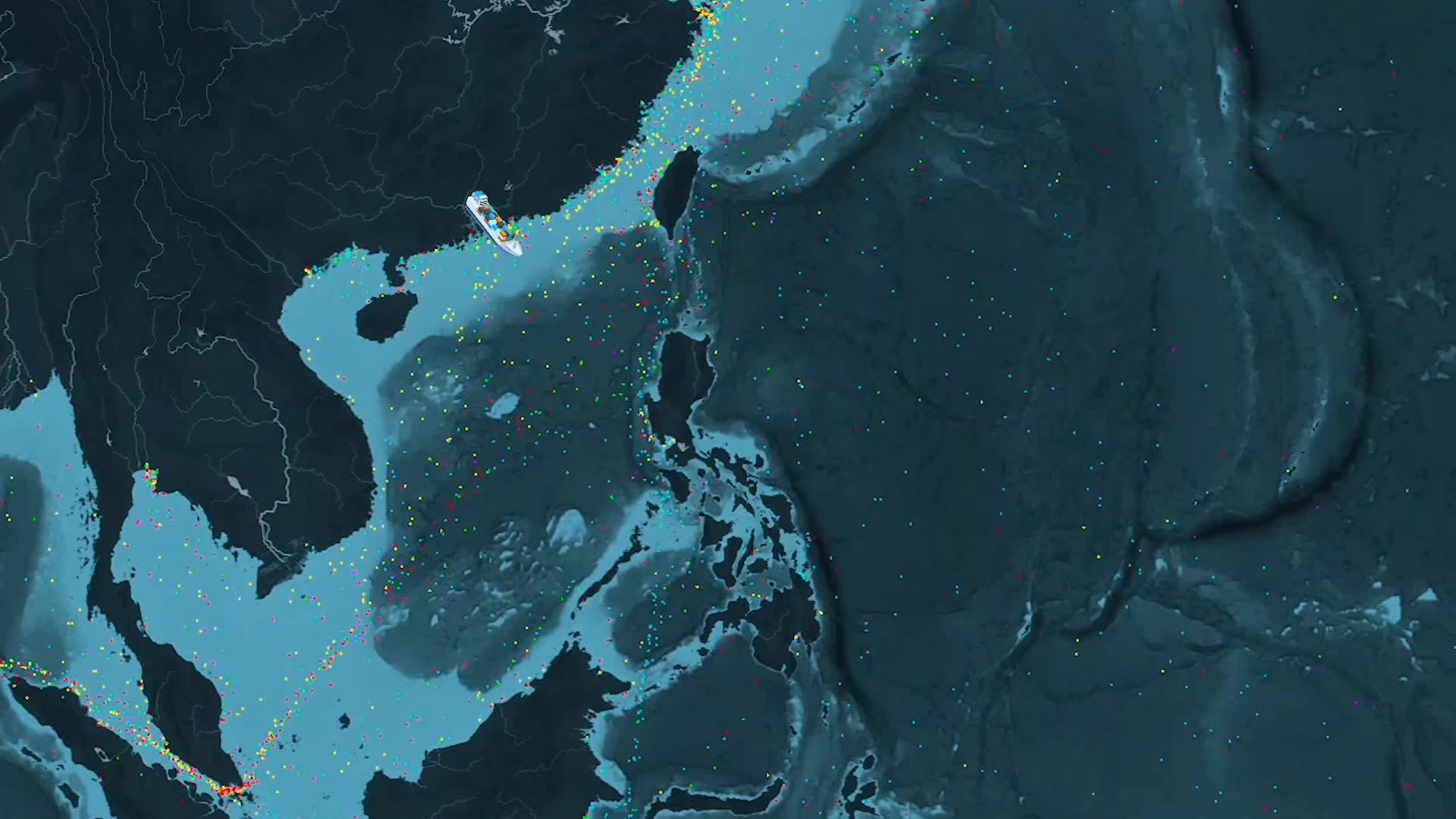

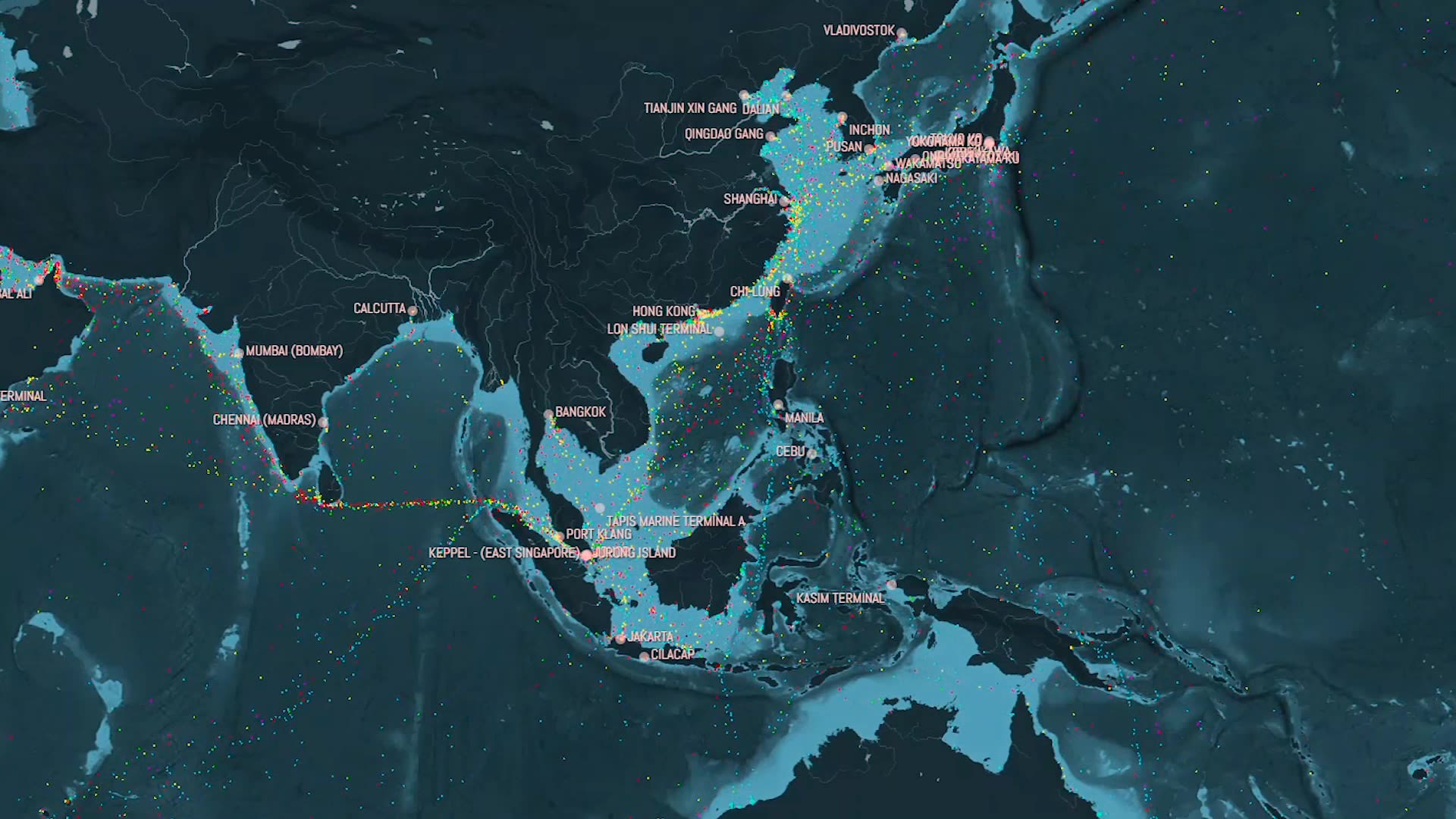

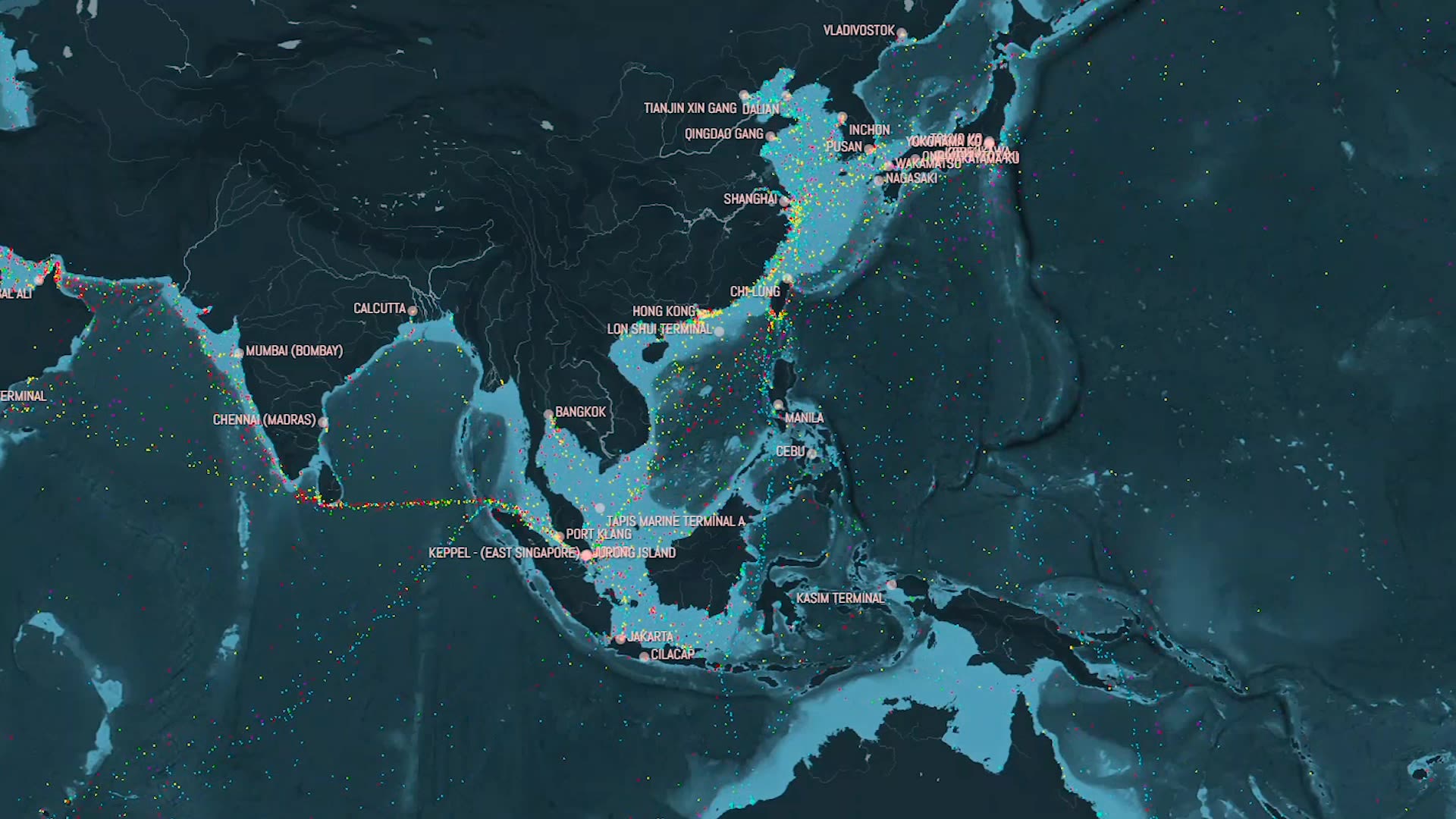

A cargo of cellphones from the port of Shekou, China will take about five days to travel to Cebu, Philippines.

The delivery will result in more than two million kilogrammes of carbon emissions,

enough to power 300 homes

for one year.

More than half of the

world's largest proprietors of

shipping vessels are from Asia.

Eco-Business explores what the region's biggest

maritime companies are doing

to lower their environmental impact.

Are Asia’s shipowners doing enough to cut greenhouse gas emissions?

By Hannah Alcoseba Fernandez | Graphics by Earn Philip Amiote

3 October 2023

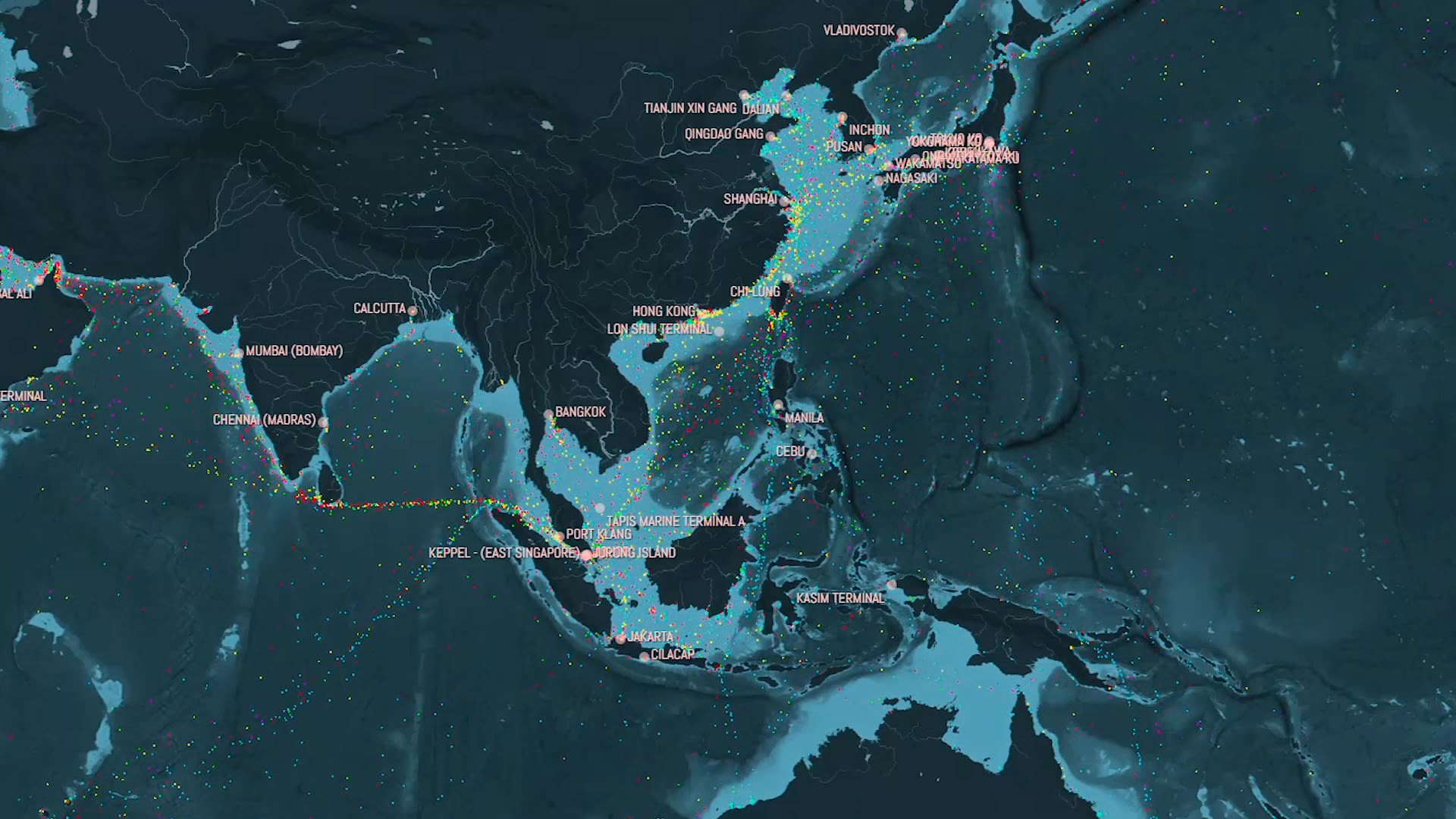

Asia is home to more than half of the world’s top ten major shipowners, based on a report released by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) on 27 September.

China is at the forefront, being the second largest fleet owner globally after Greece, in terms of the carrying capacity of a vessel. Japan’s ships can handle almost the same weight of cargo, fuel, water, and crew as China's, but only have half the quantity of its vessels. Taiwan has overtaken the United States for the first time this year, ramping up its fleet and dead weight tonnage (DWT).

Almost the entire maritime industry relies on the Republic of Korea, China and Japan to build their ships.

China, Singapore, and India provide the world’s biggest ports, while the Philippines and Indonesia are the top providers of seafarers and maritime officers.

“Asia is very much a hub for this industry, and it is vital that the shipping carriers and shipbuilders work together to respond to increasing demand and scale up their lower-emissions options for customers,” said Eric Leveridge, climate campaign manager of US-based nonprofit Pacific Environment.

If it was a country, the shipping industry would be the eighth biggest greenhouse gas (GHG) emitting nation. This is equivalent to almost three per cent of the world's emissions, about the same as Germany's.

However, shipping is not explicitly included in the Paris Agreement. The responsibility for cutting the emissions of the sector lies with the International Maritime Organisation (IMO), which is the United Nations body that regulates the safety and environmental performance of international shipping.

The IMO in July settled for an emissions target of net zero “by or around 2050”, after decades of stalled talks.

However, it did not agree on fuel standards or a shipping carbon levy, to help drive and pay for the transition.

China was a key opponent of the levy, arguing it would put a disproportionate burden on developing nations. But research by Netherlands-based consultancy CE Delft, published in the same month as the negotiations in London, shows that cutting shipping emissions by half this decade would only add some 10 per cent to the total costs of operations.

Eco-Business surveyed 10 of Asia’s biggest shipping carriers to evaluate their decarbonisation commitments. Using analysis from a study published in August by nonprofit Ship It Zero, news reports, company websites, and interviews with industry experts, we scrutinised the measures shipowners are taking to achieve their goals, in line with the IMO revised targets.

China Ocean Shipping (COSCO Shipping) is a state-owned conglomerate headquartered in Shanghai. Despite being the fourth largest maritime shipping

company in the world, it only plans to meet its carbon neutrality target by 2060.

It has committed to using shore power, which enables vessels to turn off their engines, and instead plug into the local electricity grid to power auxiliary systems while at berth. But in 2019, it paid penalties worth US$965,000 to the California Air Resources Board for air quality violations when docking at the ports of Los Angeles and Oakland from 2014 to 2017.

While the company has invested in a short-term biofuels trial for a voyage, it continues to rely on scrubbers which are installed on vessels to reduce sulfur air emissions resulting from the use of high-sulfur fuel. Most vessels are equipped with scrubbers in order to allow ship operators to continue to use heavy fuel oil. The device uses seawater to “wash” sulfur from the exhaust plume, producing wastewater that is acidic and toxic.

Evergreen Marine Corporation, a mammoth shipping line based in Taiwan, has a climate ambition of just a 70 per cent reduction in emissions by 2050.

But it has committed to shore power-compatible fleet and invested in the technology at its own terminals, despite the lack of specific targets for shore power compatibility.

It has also put in place efficiency retrofits like slow steaming, which refers to deliberately reducing the speed of cargo ships to cut down fuel consumption and carbon emissions. It has yet to invest in lower emission fuels.

Taipei-based Wan Hai has also pledged a 70 per cent reduction in carbon intensity of its fleet by 2050, and has no specific strategies for how it will achieve this aside from slow steaming.

Yang Ming, which has its main dock in Keelung, has made no concrete emissions reduction goals, but has vowed to build a monitoring system to manage fuel consumption and reduce emissions. It said that it was evaluating the possibility of developing dual-fuel engines that can perform with more sustainable alternative fuels, but no tangible measures are known.

HMM, formerly Hyundai Merchant Marine, is the largest shipping company in the Republic of Korea.

It has an ambitious short-term greenhouse gas emissions reduction target of 50 per cent by 2030, based on a 2008 baseline, as part of its blueprint to attain carbon neutrality by 2050.

The company has committed to switching its freight to readily available lower-emissions fuels, but remains reliant on liquified natural gas (LNG), a fossil fuel that releases methane, a climate agitant more potent than carbon dioxide.

It has vowed to implement efficiency retrofits and slow steaming as part of its 2030 goal, but still uses gas cleaning systems like scrubbers.

e climate than cbon dioxide.

Ocean Network Express (ONE) of Japan has an ambitious short-term carbon emissions reduction target of 70 per cent for Scope 1 emissions by 2030 from a 2008 baseline.

The company is utilising biofuels as a bridge to ammonia and methanol. It is also prioritising efficiency retrofits and slow steaming.

Mitsui OSK Lines (MOL), also based in Japan, has set a target of achieving net zero emissions by 2050.

It is chartering a methanoldual-fuel bulk carrier, which is expected to launch in 2027.

It plans to burn e-methanol, which is produced from carbon dioxide and renewable energy, as well as bio-methanol sourced from biogas, to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

Pacific International Lines, founded by Singaporean entrepreneur Chang Yun Chung, has not publicly committed to reducing criteria air pollutants in ports, and only reports its emissions for one pollutant (sulphur oxide).

The company does utilise shore power and has made some investments in the infrastructure but these initiatives appear minimal compared to other carriers.

Neither Korea Marine Transport Corporation nor China’s Zhonggu Logistics Corporation have made known any emissions reduction targets.

The green transition plans of Asia's big shipping companies are at varying stages of development, said Pacific Environment’s Leveridge, whose job includes influencing major shipping companies and shipping-reliant corporations to transition ships away from fossil fuels.

ONE has the most comprehensive pathway due to the detail in its decarbonisation plan but it is in many ways still "theoretical". HMM also has a detailed plan, but it is too reliant on LNG, he told Eco-Business.

“The other companies have limited information on how they will meet their goals, with more focus on efficiency measures than alternative fuel development,” he said.

But the responsibility of emissions reduction does not lie with shipowners alone

Vessels still need to have a source of supply for green marine fuels, essentially gas stations, to fill up. That becomes a role and opportunity for ports throughout the world, said Don Maier, associate professor of practice in supply chain management at the University of Tennessee.

Maier cited a study published by the Australian Maritime College in May which examined the ability of various ports around the world to support the international trade of hydrogen.

Hydrogen is viewed as a promising alternative fuel for decarbonising shipping because it is lightweight and vehicles can travel a long way without refuelling.

The study found 20 ports could support hydrogen trading but none of were in Asia.

However, the study did find that Japan, South Korea, and Singapore, as hydrogen importers with growing appetites for renewable fuels, may need to build port infrastructure to support hydrogen trading.

“While the readiness of the ports featured in the study are still in their infancy, additional resources and time will need to be invested in infrastructure, risk management, regulations, and training to further support global demand,” Maier said.

However, port authorities often say that the cost of investment in transition tools like shore power are too steep, said Leveridge.

There is also pushback from other stakeholders over their specific responsibilities to bring about low carbon shipping, according to Leveridge:

Retailers say green offerings are too expensive, and shipping carriers often say there is not enough demand from their customers or investment from ports.

“We are trying to break through the finger-pointing and encourage investment from all stakeholders," he said. "We want to have more engagement with shipping companies so that they understand that as their customers are creating their own organisational decarbonisation goals, they need carriers to increase their lower- and zero-emission offerings as well."