Stuttering progress

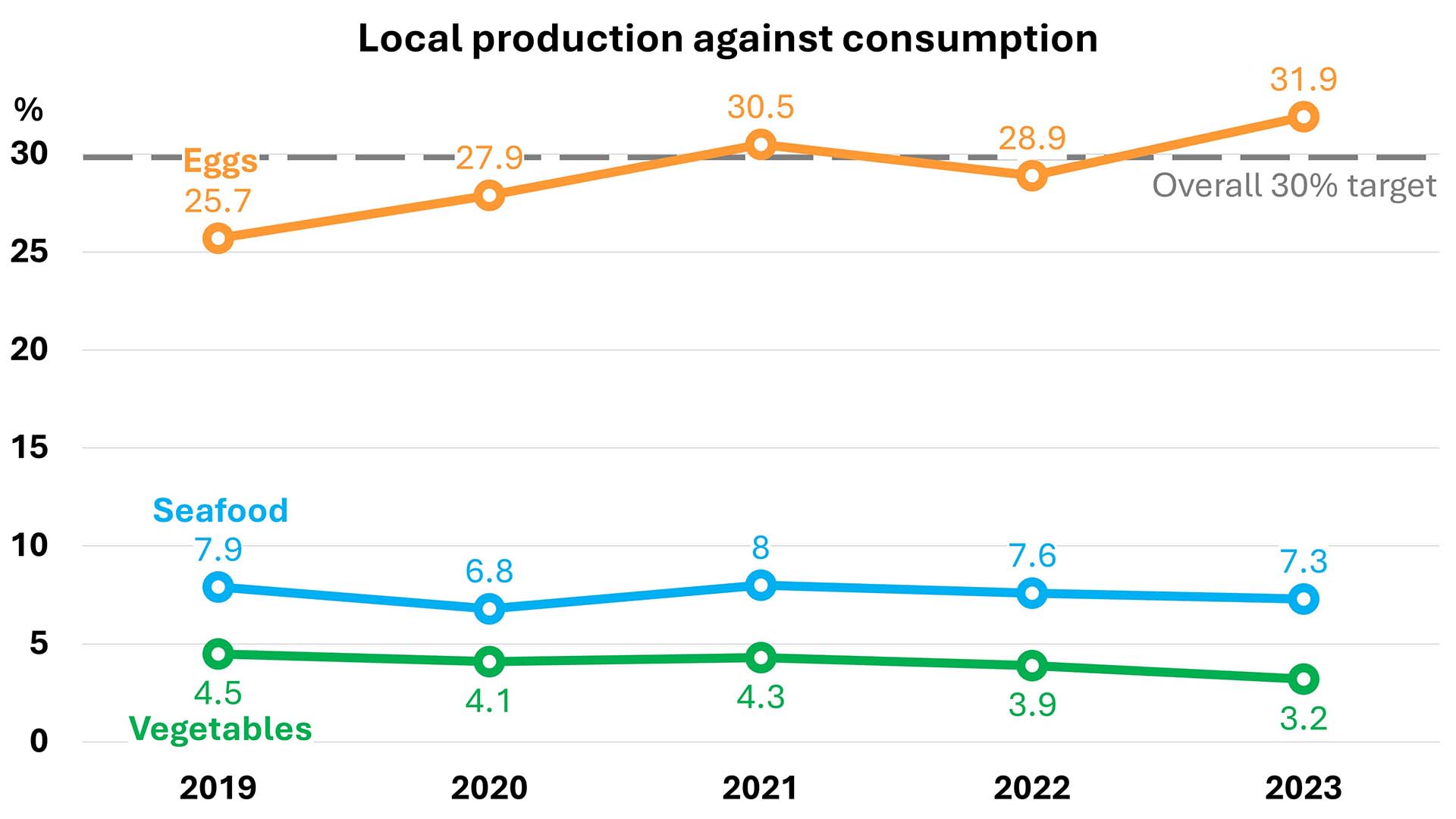

Local food production has stayed at under a third of where Singapore wants it to be.

Home | Chapter 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6

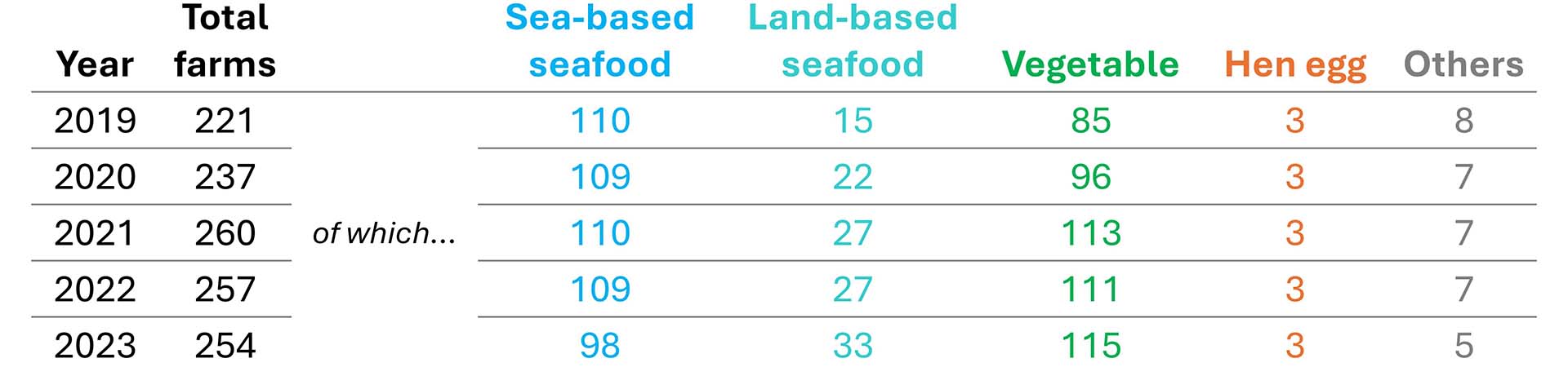

The Singapore Food Agency (SFA) keeps a close eye on three types of food for domestic production, based on local diet norms and production viability – chicken eggs, seafood and leafy vegetables.

Data: Singapore Food Agency’s annual food statistics reports.

Data: Singapore Food Agency’s annual food statistics reports.

Egg production is doing well, even as the country’s fourth farm faces delays in its opening, with almost 32 per cent of consumption met locally in 2023. But vegetable and seafood numbers continue to drop from already low bases, to 3.2 per cent and 7.3 per cent.

In absolute figures, egg production rose 12 per cent year-on-year following farm upgrades. Vegetable and seafood production dropped 15 and 8 per cent respectively, from Covid-19 delays, economic headwinds, as well as higher energy and manpower costs, SFA said in its latest tally published last week.

Beyond the overall 30 per cent goal, there are no targets for individual food sectors. However, local food production has remained under 10 per cent, with the rest met with food imports globally.

Data: Singstat, Singapore Food Agency.

Data: Singstat, Singapore Food Agency.

Since the “30 by 30” production goal was announced in 2019, the number of farms has risen sharply, mainly from new vegetable and land-based seafood facilities. But since 2021, the numbers have gradually fallen – lately caused by a drop in sea farms.

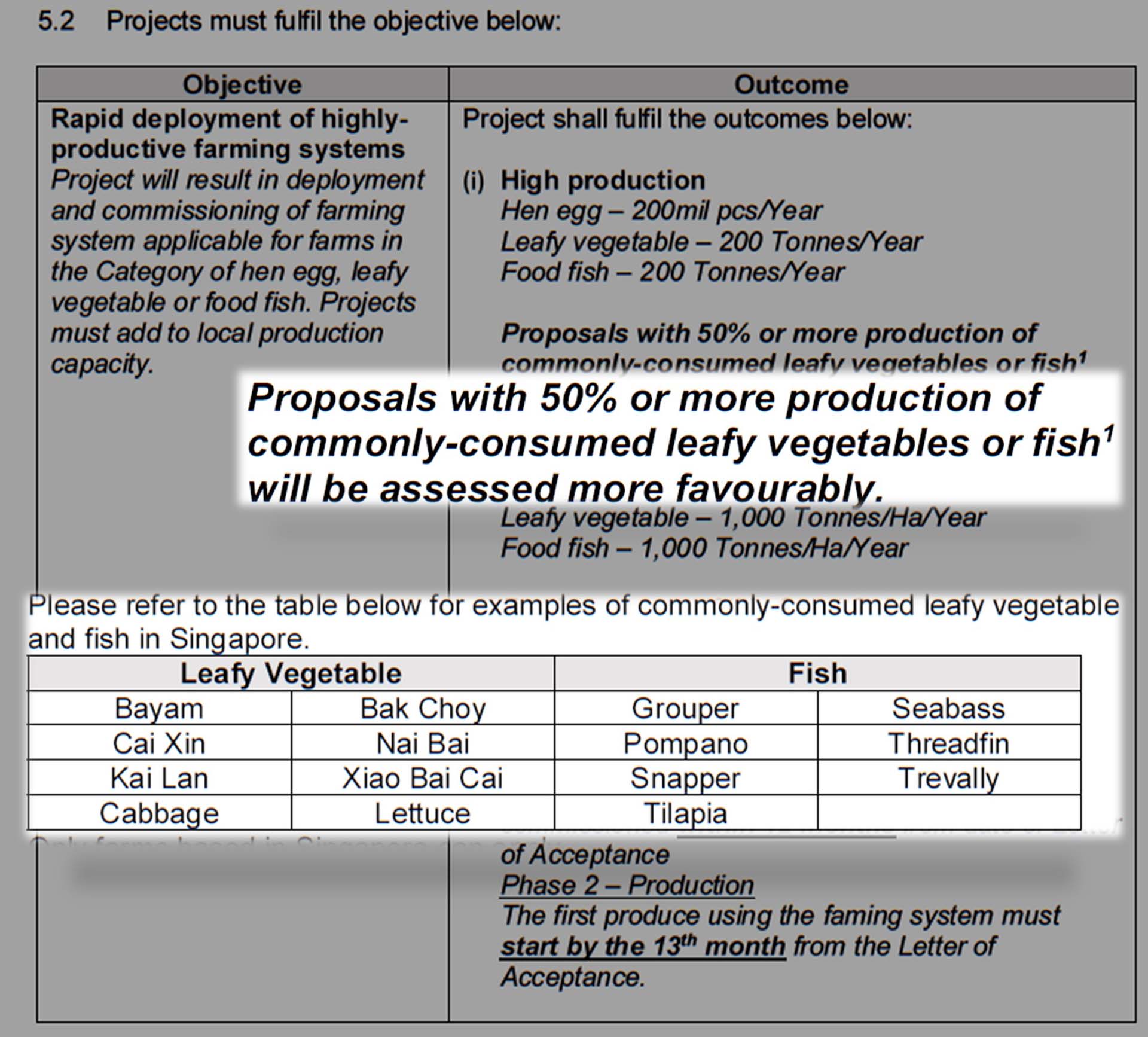

Support measures have returned mixed success. In 2020, the Singapore Food Agency launched a “30x30 Express” grant to help local growers speed up new developments amid the Covid-19 pandemic. Eight farms – seven vegetable and one egg facility – were provided almost S$40 million (US$30 million) to ramp up production capacity with a deadline of just under two years.

Of the awardees, two vertical farms – VertiVegies and I.F.F.I – are out of the game. VertiVegies never built its facility; it relinquished its land parcel after missing construction deadlines, local daily The Straits Times reported last month. I.F.F.I, operational up till 2023, has closed down and its property is being seized by Singapore’s industry agency JTC Corporation, per court documents seen by Eco-Business in April.

Other awardees have also faced challenges. For instance, Growy’s farm took longer than two years to reach commercial production, as the asset switched hands multiple times since its original German owner snagged the grant in 2020. Local greenhouse Livfresh returned part of its roughly S$4 million (US$3 million) grant after missing development deadlines as its equipment was stuck overseas due to a global shipping jam. But the farm has since been completed, core operations are profitable and there are plans to expand, founder Karthik Rajan told Eco-Business.

Progress has also been patchy in the seafood sector. Apollo Aquaculture Group, which was developing an eight-storey indoor fish farm with an annual output capacity of 2,700 tonnes, has been under judicial management since mid-2022. Its facility in the West of Singapore now sits vacant.

Apollo Aquaculture’s vertical fish farm in Lim Chu Kang now sits unused.

Apollo Aquaculture’s vertical fish farm in Lim Chu Kang now sits unused.

Offshore, even as more sea space is availed for fish farming, Barramundi Group, which had been operating in Singapore since 2008 and harvested nearly 400 tonnes of fish in 2022, is planning its exit to focus on its Brunei operations. It cited the lack of supporting infrastructure in Singapore to The Straits Times.

Along the Johor Strait, over two-decade-old fish farm Ah Hua Kelong is not confident it will last the next few years due to the intensifying price competition from bigger local entrants and Malaysian counterparts. The farm has no near-term plans to expand and has even turned down some investors as it is simply trying to survive, its co-founder Wong Jing Kai, or Kai, told Eco-Business.

Seafood production at the kelong (Malay for a wooden offshore platform) has more than halved from a couple of years back to around 30 tonnes annually, despite efforts to sustain demand for its produce through setting up restaurants on the mainland – including a newly launched farm-to-table hawker concept – and keeping prices unchanged. The discouraging landscape has made Kai, who ventured into the industry a decade ago as a young upstart with a vision to bridge the gap between local seafood and Singaporeans, feel beaten up. “Like no hope already. If you talked to me five years ago, I think I would be quite enthusiastic,” he said.

Wong Jing Kai, 35, who has run the offshore fish farm for a decade, is not confident it will be around for much longer. Images: Ah Hua Kelong

Wong Jing Kai, 35, who has run the offshore fish farm for a decade, is not confident it will be around for much longer. Images: Ah Hua Kelong

Many smallholders like Kai find it hard to break into Singapore's retail sector, many of which prioritises affordability and a reliably large supply volume. The high cost of local production still shows in the prices of goods that have made supermarket shelves, with the vegetables sector appearing the most undercut by imports. Eggs, meanwhile, are on general price parity with common Malaysian offerings.

Grocery prices at a Fairprice supermarket in mid-May 2024.

Grocery prices at a Fairprice supermarket in mid-May 2024.

Singapore’s push for production volume amid such challenges have vexed some farmers, who say their voices have not been reflected in existing policy.

For instance, some vegetable farmers point to a clause within the 30x30 Express grant that prioritises applicants with over half their output being common crop varieties, which are mainly Asian leafy greens. They said this was an unrealistic expectation, especially against the parallel ask to adopt more technology, given the high costs of production and low market price for Asian greens.

The 30x30 Express grant had prioritised common local produce, many of which cannot fetch high prices on the market.

The 30x30 Express grant had prioritised common local produce, many of which cannot fetch high prices on the market.

“I think the civil servants need to go down and listen to the real issues on the ground, and understand the business models that are working and not working,” Veera said. He believes farmers would be better off trying to displace high-end salad products in supermarkets hailing from Australia and Europe.

Herein lie the conundrums. Focusing on common local produce makes sense for food security, but is not something all farmers can confidently deliver. Competing in a mass market makes sense for securing demand, but Malaysian, Chinese and other regional imports often compete better on price. The search for a game changer continues.