The elusive agricultural hub

Will Singapore’s second, larger attempt at an innovative agri-food zone work out?

Home | 2 | 3 | Chapter 4 | 5 | 6

Singapore is known for developing world-class industrial hubs. Apart from its downtown financial centre, on its western fringe lies a thriving biomedical park. Further at the end of the mainland is Jurong Island, one of the world’s top oil refining locations.

Pressured to ramp up local food production, farmers too have been calling for more national infrastructure so that scale can be achieved.

Jack Moy, chief executive of indoor vertical farm Sustenir, believes that growers should not need to bear the burden of building their own farms.

“The capability to build a farm and to run a farm is different. So why is [one] company doing both?” he said, adding that current high interest rates make it difficult for farmers to develop new facilities. Government-built farms will “alleviate a lot of pressure” on the farmers, Moy said.

There are similar sentiments in the aquaculture space. Tan Ying Quan from Barramundi Group said having a nationalised hatchery and nursery that focuses on supplying high-quality fingerling can help the industry operate with greater predictability and lower disease risk.

But a hub concept for Singapore’s agriculture industry remains elusive, for now, despite big plans in the works.

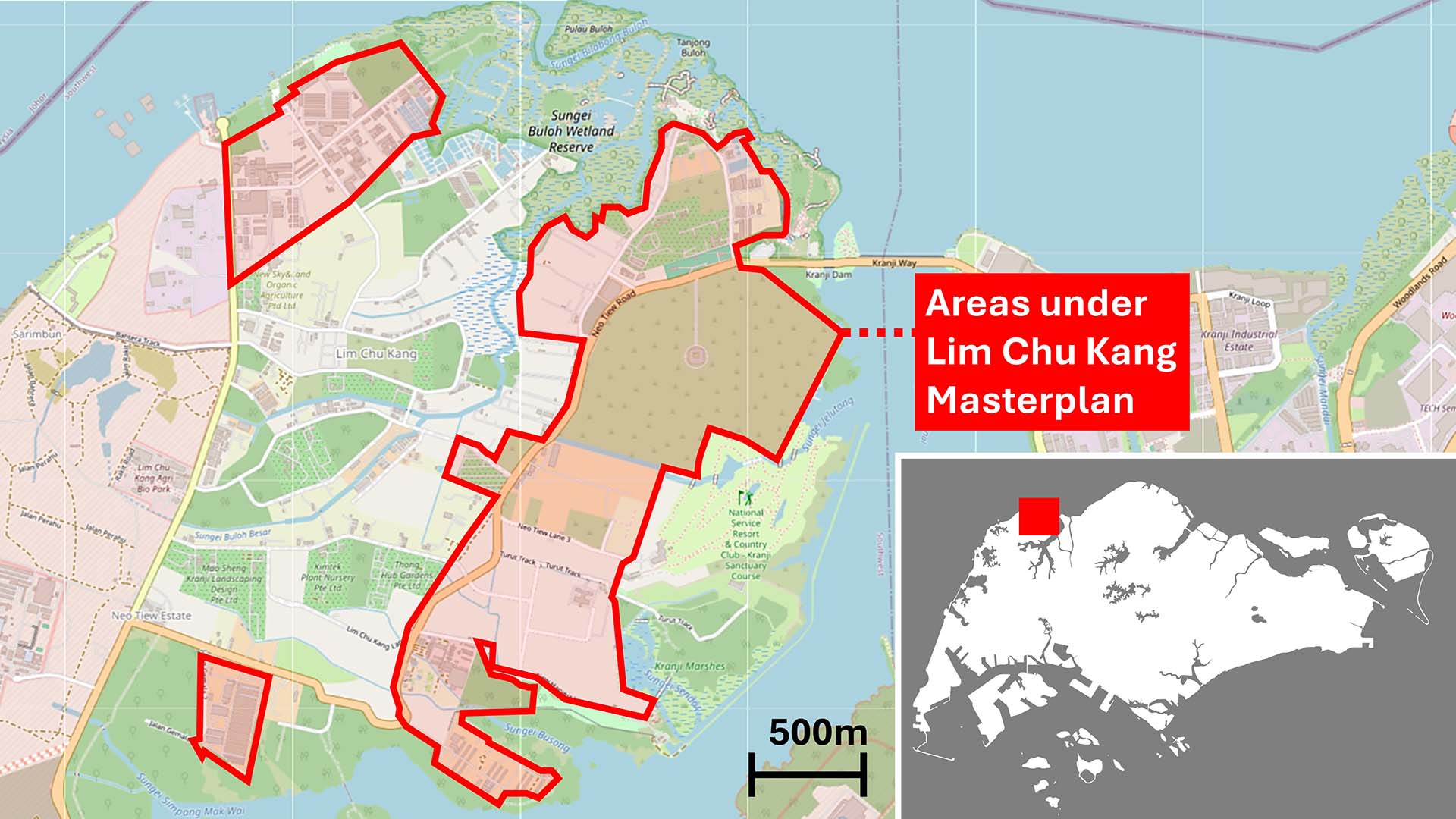

In 2020, Singapore Food Agency (SFA) announced its intention to transform 390 hectares of Lim Chu Kang, Singapore’s last major agricultural estate on its northwestern coast, into a “high-tech, highly productive and resource-efficient agri-food cluster”, that could triple the current food output capacity. There were ideas for farm by-products to be used as inputs for other facilities – a page out of Singapore’s vaunted petrochemical hub on Jurong Island.

Much of Singapore's existing farm plots in the Lim Chu Kang estate are under a redevelopment plan, marked in red. Map: OpenStreetMap. Reference: SFA.

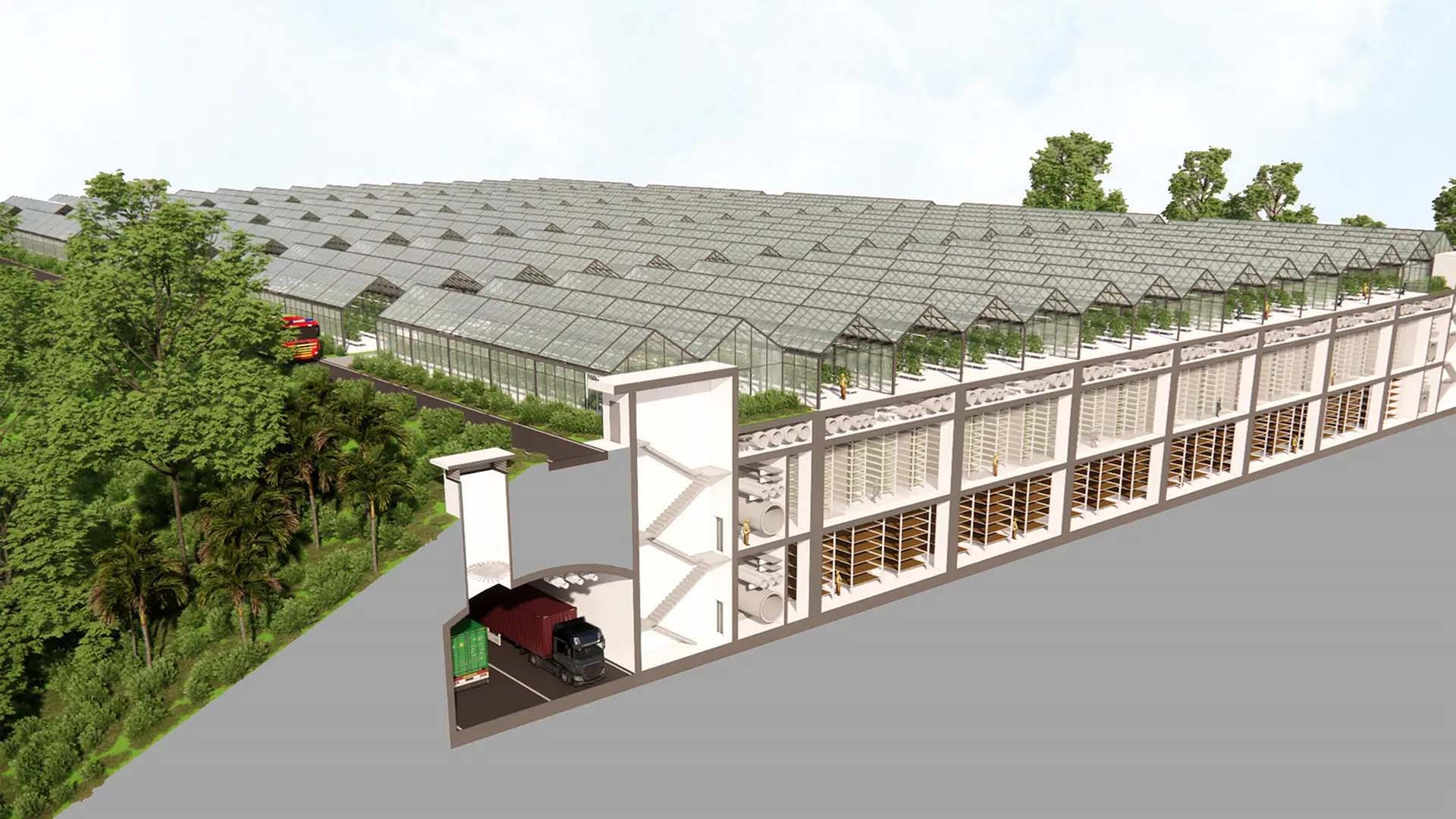

Stacked farm concept for Lim Chu Kang. Image: Ramboll.

Last September, further concepts of stacked farms were unveiled, with basement indoor vegetable and mushroom farms overlaid with greenhouses on the surface. District cooling would provide cheaper, shared access to temperature control. On the drawing board are also land-based fish and crustacean farms, along with shared utility and transport tunnels, shared Jan Westra, strategic business developer at Dutch greenhouse tech firm Priva, which is involved in the planning works.

The key issue is to ensure frugality with water and energy, given the high utility prices.

“In the United Arab Emirates or Saudi Arabia, energy prices are so low that you can build anything you want and run it on cheap gas, cheap electricity,” he said, referring to Middle East states that also have similar food tech ambitions. Evaporative cooling systems, often more energy efficient, can be used in dry desert environments. But not in Singapore, he added.

The stacked farm estate in Singapore will also need to properly treat its effluents, given its proximity to nearby marshes and the Sungei Buloh wetland reserve that shelters global migratory birds. Best-in-class technologies will be required for every farm type, Westra said, adding that all these requirements meant Singapore’s food production ambition is the biggest challenge that he has ever taken on.

For now, beyond the concept sketches, much of the details of the Lim Chu Kang redevelopment exercise remains unclear, with planning stretching past an initial deadline of end-2023. This month, senior minister of state Koh told local media that planning works may only be finalised by end of the year, or early next. Westra said there had been plans to get a stacked farm completed in the northern sector of the precinct by early 2025, but SFA did not comment when asked.

The Lim Chu Kang effort is in fact Singapore’s second attempt in recent years to develop a high-tech agricultural hub. There had been an earlier attempt at developing an 18-hectare “Agri-Food Innovation Park” on the outskirts of Lim Chu Kang, which was to open in stages from 2021. Forest clearing had started in 2020, but development now appears to have halted, with the barricaded plot turning back into woodland. SFA did not provide an update to the status of the venture, or if any lessons had been drawn from the earlier project, when asked.

The land set aside for the Agri-Food Innovation Park sits undeveloped today.

The land set aside for the Agri-Food Innovation Park sits undeveloped today.

Professor Veera Sekaran said that for the latest Lim Chu Kang initiative to work, authorities could reference how Singapore manages its water and sanitation works – with the government providing much of the oversight and facilities, while some desalination and treatment plants are under joint management with private developers.